On the 60th anniversary of SingaporeŌĆÖs independence, archival accounts and historian insights shed light on the tense, covert negotiations that led to the ŌĆ£bloodless coupŌĆØ of 9 August 1965, ending a two-year union with Malaysia.

On the morning of 9 August 1965, Singaporeans woke to news that would change their history.

At 9.30am, in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman told Parliament that Singapore was leaving the Federation of Malaysia. Barely three hours later, in Singapore, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew appeared on television.

His voice broke, his eyes brimmed with tears, and he called it ŌĆ£a moment of anguishŌĆØ ŌĆö the end of the merger he had fought for just two years earlier.

For decades, the story would be told as a sudden expulsion.

Yet, archival records, memoirs, and even a 1965 U.S. Embassy telegram reveal a more complex truth: the separation was the outcome of secret talks, calculated risks, and decisions made by a handful of leaders under intense political pressure.

The road to merger

The Malaysia Agreement, signed on 9 July 1963, was meant to reunite Singapore, Sabah, Sarawak, and Malaya. For Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP, merger was both a nationalist goal and a political necessity.

As historian Dr Thum Ping Tjin explained in a 2015 interview, ŌĆ£In 1957, a survey found 90% of Singaporeans in favour of merger. It wasnŌĆÖt just an ideal ŌĆö if you wanted to win elections, you had to be openly for reunification with Malaya.ŌĆØ Lee himself saw merger as a platform to influence politics in Kuala Lumpur and perhaps rise to lead a united Malaysia.

But the terms of merger were not equal. Singaporeans could only vote in Singapore. PAP politicians could not contest mainland seats. These restrictions limited LeeŌĆÖs ambitions from the start.

Early rifts

On 31 August 1963 ŌĆö just over two weeks before MalaysiaŌĆÖs formal formation ŌĆö Lee declared SingaporeŌĆÖs unilateral independence and called a general election. This blindsided Tunku Abdul Rahman.

The September 1963 elections pitted PAP against MalaysiaŌĆÖs ruling coalition, Barisan Nasional (BN). BN lost every seat it contested, including three Malay-majority constituencies in Singapore. For Tunku, it was a warning: Malay voters on the island were not reliably UMNO supporters.

In 1964, PAP broke another informal pledge by contesting 11 mainland seats in MalaysiaŌĆÖs general election. Only Devan Nair won ŌĆö in Bangsar ŌĆö but the move was seen as a direct challenge to UMNOŌĆÖs political dominance.

1964: Riots and mistrust

Relations soured further with the 21 July 1964 racial riots in Singapore. Scores were killed, hundreds injured, and mutual trust eroded.

Dr Thum notes that Lee, who had once used racial arguments to push for merger, now began championing a ŌĆ£Malaysian MalaysiaŌĆØ ŌĆö equal rights regardless of race.

For UMNO leaders, this reversal appeared opportunistic and threatening.

In December 1964, during a golf game, Tunku proposed to Goh Keng Swee a looser federation: Singapore would leave MalaysiaŌĆÖs Parliament but still pay for defence and surrender control over Malay affairs on the island. Goh rejected the terms as politically unacceptable.

1965: A choice takes shape

By mid-1965, the political relationship was beyond repair. In June, Lee delivered his ŌĆ£Malaysia for MalaysiansŌĆØ speech at the Malaysian Solidarity Convention, earning his wife Kwa Geok ChooŌĆÖs praise but further alienating UMNO.

In July, while recovering from illness in London, Tunku decided Singapore must leave.

On 15 July, Malaysian ministers Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman and JaŌĆÖafar Albar met Goh in Kuala Lumpur. The meeting began as a criticism of Lee but turned into a proposal for separation. Goh agreed in principle, warning that delay would only strengthen LeeŌĆÖs position.

Only Lee, Goh, Law Minister E.W. Barker, and Finance Minister Lim Kim San were aware. On 26 July, Goh arrived with a handwritten note from Lee authorising him to negotiate. Barker began drafting the separation agreement.

Risk and secrecy

The talks carried enormous personal risk. If they failed, Goh and Barker could be charged with sedition under MalaysiaŌĆÖs constitution. One telephone conversation between Goh and Lee was conducted in halting Mandarin to keep the operator from understanding.

On 3 August, Tun Abdul Razak presented TunkuŌĆÖs conditions: Singapore must contribute to MalaysiaŌĆÖs defence budget and avoid foreign defence pacts. Goh sidestepped these points, saying Singapore lacked resources to build a military.

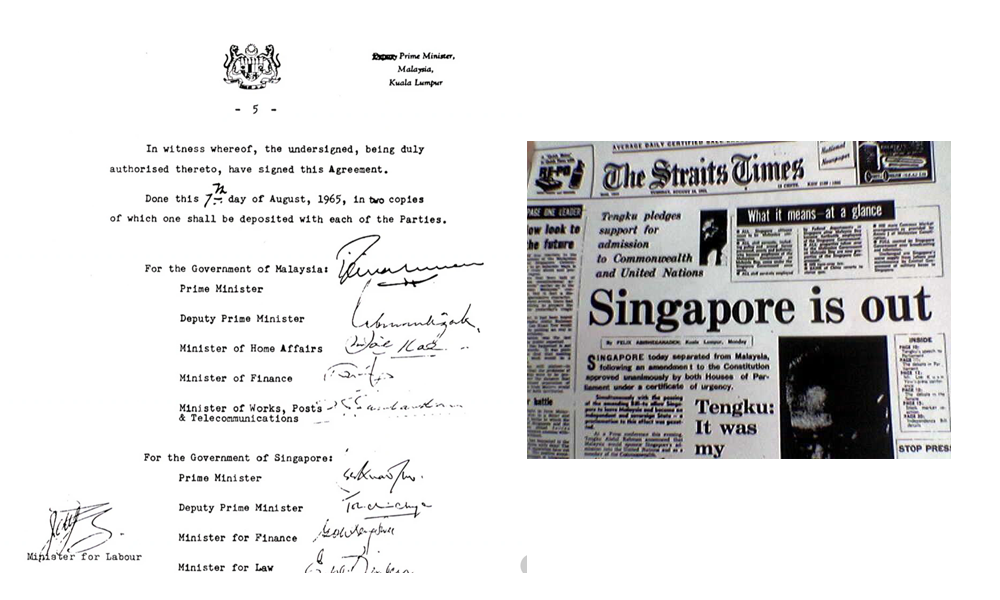

By 6 August, the draft was nearly final. That night, Goh and Barker travelled to Kuala Lumpur to complete the deal. They negotiated late into the night. When Barker returned, Lee reportedly thanked him for delivering ŌĆ£a bloodless coupŌĆØ.

Cabinet resistance

On 7 August, Lee revealed the plan to the PAP Cabinet. Opposition came from Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam and Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye, who saw separation as a betrayal of Sabah and Sarawak allies. They even considered contacting communist militants to resist a Malaysian takeover ŌĆö an idea Lee rejected.

By 8 August, preparations moved quickly. PAP leaders spread the news to party activists across Malaysia. That night, the separation documents were printed in secrecy in Serangoon. The British were informed only after signatures were secured.

9 August 1965: Announcements in two capitals

At 9.30am, Tunku told the Malaysian Parliament that Singapore was leaving. The constitutional amendment passed, but only after Tunku warned Alliance MPs he would resign if they refused.

According to the U.S. Embassy telegram, this ultimatum damaged TunkuŌĆÖs image as a unifier but cemented his dominance over the Alliance. Only one senior figure ŌĆö UMNO Secretary-General JaŌĆÖafar Albar ŌĆö defied him, and was forced to resign.

At noon, Lee addressed Singaporeans in an emotional broadcast. Behind the public grief was a political reality: by leaving Malaysia, Lee secured unchallenged leadership in Singapore.

Shockwaves in Malaysian politics

The separation left no one fully satisfied. The U.S. Embassy reported that only the communist-influenced Socialist Front and some far-right Malay nationalists appeared pleased.

Malay extremists in UMNO were bitter. Some younger members might have followed Albar in a revolt, but he publicly pledged loyalty to Tunku while quietly working to strengthen his position.

Among the Chinese political class, the reaction was sharp. MCA youth were furious that their leaders had allowed what they saw as the ŌĆ£ejectionŌĆØ of 1.5 million Chinese from Malaysia, weakening their bargaining power.

MCA leader Tan Siew Sin told party youth that separation was a tragedy but unavoidable, placing blame on Lee and urging unity.

Economic calculations

On paper, Malaysia lost significant resources with SingaporeŌĆÖs departure. The loss of promised development funds for Borneo was cited as a blow, but cooperation had already been minimal. SingaporeŌĆÖs commitment to a M$150 million loan was conditional on labour access for Borneo ŌĆö a point never agreed.

Economic ties, however, could not be severed easily. While tariffs and quotas on Malaysian goods caused initial animosity, both governments recognised their interdependence. A ŌĆ£common marketŌĆØ remained possible, and many businessmen were optimistic trade relations could be repaired if politics stayed out of the way.

Nation-building in Singapore

For Lee, independence meant both a political victory and a new challenge. Dr Thum notes that Lee had to abandon the Malayan identity he had championed since 1959 and instead emphasise a distinct Singaporean identity.

Policies shifted towards English and Chinese as dominant languages, while Malay remained the national language in name. Economically, Singapore moved towards an open, export-driven model, free from Kuala LumpurŌĆÖs protectionist policies.

Sixty years later

Today, Singapore marks its 60th National Day with a clearer understanding of 1965ŌĆÖs events. The separation was not a sudden ejection but the outcome of covert manoeuvres, calculated risks, and political trade-offs.

It was, in LeeŌĆÖs words, a ŌĆ£bloodless coupŌĆØ ŌĆö and one that set both nations on divergent but enduringly connected paths.