In 1965, few gave Singapore a chance. Thrust into sudden independence, devoid of natural resources, rocked by communal tensions and political isolation, the island city-state seemed destined to fail. Yet by the 1990s, Singapore had transformed into one of the most dynamic and prosperous economies in the world.

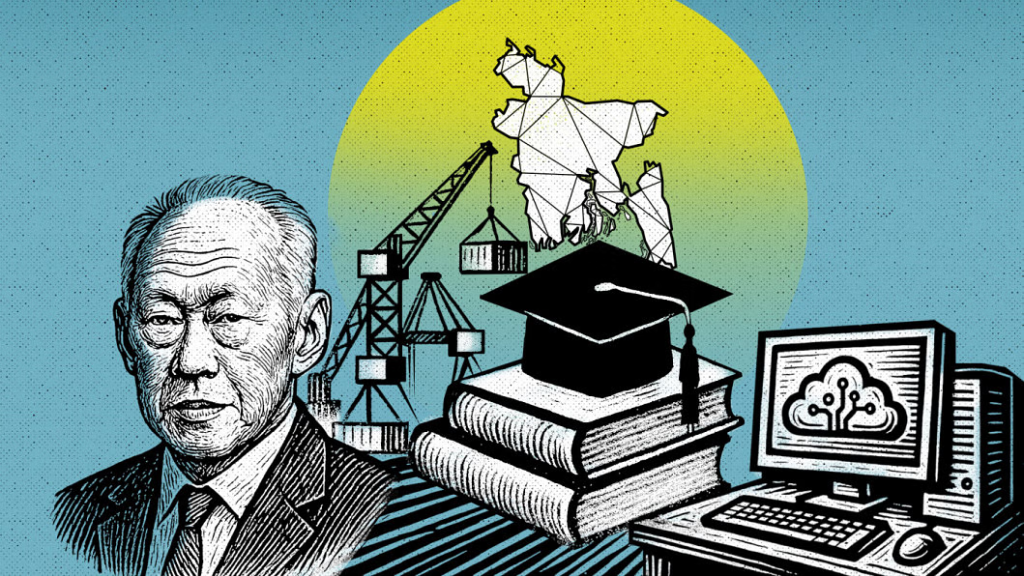

At the helm of this improbable rise was Lee Kuan Yew. His leadership combined bold vision, ruthless pragmatism, and an uncompromising commitment to long-term national development. His immediate assurance to his people was to build a Singapore that would be recognisable and identifiable. But beyond charisma and control, Singapore’s rise offers a more replicable asset for a country like Bangladesh today: an economics-driven blueprint for navigating uncertainty and achieving productivity-led growth.

One of my favourite professors at Harvard Business School, Rafael Di Tella, argues that sustainable prosperity depends not just on the quantity of inputs like labour or capital, but on how efficiently those inputs are used—a concept known as Total Factor Productivity (TFP). TFP captures gains made through better resource allocation, continual innovation, and institutional efficiency. If Bangladesh is to achieve its vision of becoming a developed economy by 2041, it must shift its focus from merely adding more inputs to increasing the productivity of everything it already has.

Singapore internalised the TFP principle early. Its economic planners understood that to move up the value chain, the country had to not only produce more, but produce smarter. In the 1970s, the focus was on low-cost assembly and employment generation. By the 1990s, the economy had successfully pivoted to high-value sectors such as biomedical sciences, precision engineering, and financial services. This shift wasn’t accidental—rather, it was the outcome of deliberate choices to enhance skill levels, embrace foreign technology, and streamline policy execution.

For Bangladesh, this means a national growth narrative that is no longer input-driven (labour-intensive, consumption-based), but TFP-driven. To do so requires urgent investment in vocational and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education, logistics and digital infrastructure, and a regulatory regime that reduces friction and enhances operational efficiency across industries.

TFP growth cannot occur in a vacuum. It depends on institutions that can allocate resources effectively and adapt to new innovations continuously. Singapore’s institutions—particularly the Economic Development Board (EDB)—functioned like strategic investors, not just administrators. Civil servants were rotated across ministries, incentivised through globally competitive compensation, and held to performance standards often exceeding those of the private sector.

Lee Kuan Yew understood that if you want efficiency, you must first reward competence and enforce accountability. This institutional depth made Singapore attractive not just for its infrastructure, but for the predictability and transparency of its policy environment.

Bangladesh must now build this same institutional muscle. Agencies like Bangladesh Investment Development Authority, Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority, and National Board of Revenue must evolve from being procedural bottlenecks to becoming proactive enablers of growth. Digitisation, depoliticisation, and performance-linked governance must replace outdated practices. Stronger institutions are not a political luxury. They are economic imperatives for sustained productivity growth.

A central element of Professor Di Tella’s productivity framework is efficient resource allocation: channelling capital and labour into sectors with the highest potential return. Singapore mastered this through industrial policy that was both targeted and technocratic. Temasek Holdings and GLCs (government-linked companies) didn’t crowd out the private sector. Instead, they filled gaps, seeded innovation, and supported long-term competitiveness.

This approach delivered compounded TFP growth over decades—not by trying to do everything, but by doing the right things well.

It’s time for Bangladesh to move in this direction. Instead of indiscriminate subsidies or politically driven mega-projects, we should focus on a few catalytic sectors such as electronics, medical devices, agro-processing, software, and light engineering, where Bangladesh has comparative potential. Coordinated support in the form of skills training, infrastructure, tax incentives, and market access must be orchestrated by a coherent industrial strategy—not a collection of unaligned ministries.

TFP also depends on the quality of investment, not just its quantity. Singapore’s high domestic savings—mobilised through the Central Provident Fund (CPF)—were reinvested in housing, infrastructure, and technology, reducing its dependence on volatile external debt.

Bangladesh’s growing external debt and low national savings rate are warning signs. A contributory pension system, linked with sovereign investment funds, could unlock domestic capital for long-term infrastructure and innovation funding—two core enablers of TFP. Financial stability is not just about macroeconomics. It is about ensuring that scarce capital is deployed productively and transparently.

One of the most underappreciated drivers of Singapore’s productivity was its predictable, rule-based environment. Investors knew what to expect. Policies weren’t reversed overnight, and governance wasn’t held hostage to electoral calculations. While Singapore’s political model may not be directly replicable, the principle of decoupling long-term economic strategy from short-term politics is essential.

Bangladesh must explore institutional frameworks that protect economic priorities from partisan fluctuations. A bipartisan fiscal council, an empowered planning commission, and a non-partisan sovereign investment board could insulate key economic decisions and build investor confidence over time.

Bangladesh is not Singapore—and it doesn’t need to be. Our scale, democracy, and socio-political dynamics are distinct. But the economic logic of Singapore’s transformation, led by TFP, is universal.

Lee Kuan Yew famously said, “I always tried to be correct, not politically correct.” Bangladesh needs a similar mindset. It’s time to move from populist impulses to purposeful planning. From siloed projects to coherent strategy. From incremental input growth to exponential productivity gains.

If Singapore could leap from uncertainty to unmatched success, so can we. The playbook is open. The path is proven. The only variable left is our will.